Finance - VIII

Interest rates

9 Jan 2025

Supply and demand for loanable funds

Loanable funds are money made available by lenders to borrowers. Both parties are willing to lend or borrow money if they can expect to earn a satisfactory return. Return results may differ due to inflation, default risk, and non-sound investments.

Interest rate is the price of loanable funds, determined by the supply and demand for loanable funds (i.e. loanable funds theory). Some examples of how interest rates are adjusted are:

- when businesses are optimistic about the future, they borrow more money, increasing the demand for loanable funds, and interest rates rise;

- when inflation is high, lenders demand higher interest rates to compensate for the loss of purchasing power, whereas borrowers may cut back on borrowing, reducing the demand for loanable funds.

Interest rates for loanable funds have varied throughout the history of the US. For example, interest rates typically rise during periods of post-war economic expansion (e.g., after the Civil War) to finance reconstruction efforts. In general, interest rates (both long-term and short-term) tend to rise during periods of economic expansion and fall during recessions.

Some sources of loanable funds:

- individual and corporate savings (e.g. pension funds, retained earnings);

- deposit expansion by banks;

- Fed open market operations (e.g. buying government securities).

Factors affecting the supply of and demand for loanable funds:

- volume of savings: when incomes rise, people save more; tax rates also affect savings; older people have more savings than younger people;

- expansions of deposits by banks: lending policies and reserve requirements affect the amount of deposits that can be lent out;

- liquidity attitudes: lenders are more willing to lend when they expect to be repaid, i.e. when economic conditions are good;

- effects of interest rates: large changes in interest rates can affect the supply of and demand for loanable funds; for example, individuals are more willing to borrow when interest rates are low;

- government borrowing: when the government borrows more, the supply of loanable funds decreases, increasing interest rates.

Components of market interest rates

In addition to supply and demand, interest rates area also affected by other components. The market interest rate of a loan consists of:

- real interest rate: the rate of return on an investment when no inflation is expected;

- inflation premium: the additional expected return to compensate for inflation over the life of the loan;

- default risk premium: the additional expected return to compensate for the risk of default;

- maturity risk premium: the additional expected return to compensate for the risk of interest rate changes over the life of the loan; for example, rising market interest rates cause the value of all outstanding debt instruments to fall;

- liquidity ppremium: the additional expected return to compensate for the risk of not being able to sell the loan at a fair price.

Other financial assets share similar premiums, though they may also include their own unique premiums. For example, stocks have a stock risk premium to compensate for the risk of investing in stocks instead of other financial assets (e.g. bonds).

Risk-free interest rates are difficult to determine, because, in pratice, all investments have some risk. Still, it is possible to estimate the risk-free rate by using the interest rates of some other low-risk debt instruments as proxies. For example, we can estimate the risk-free rate by looking at the interest rate of government bonds.

Default risk-free securities: US Treasury debt instruments

In the US, Treasury debt instruments are typically considered to be free of default risk (or at least very low risk). Short-term government securities are the closest approximation to risk-free securities, because they are free of both default risk and maturity/interest rate risk. Government securities are also highly liquid, thus they are considered to be free of liquidity risk.

One use of this information is the estimate the inflation premium. For example, suppose that the real interest rate is 1% (we can typically obtain this information by looking at historical data), and that the market interest rate for a 1-year (or any short-term duration) government security is 3%. Since short-term government securities are considered to be free of default risks, maturity risks, and liquidity risks, the inflation premium is 3% - 1% = 2%.

Marketable securities

Marketable government securities are government-issued debt instruments that can be bought and sold on the open market. Many financial institutions maintain markets for these securities, or at the very least they can help route orders to institutions that do. Initial offerings of new securities are often made through Treasury auctions.

Treasury bills are issued with maturities of up to one year. For example, 91-day T-bills are issued every week. The reason they are offered weekly is to ensure that there is always a liquid market for them: new T-bills are issued regularly as old ones mature.

When the Treasury lacks funds to cover its expenditures, new T-bills are issued. Conversely, when the Treasury has excess funds, existing T-bills are retired without being replaced. This way, the Treasury can manage its cash flow and avoid running out of funds. The Treasury also issues T-bills in response to federal budget surpluses and deficits.

T-bills are issued on a discount basis (the purchase pays less than the face value of the bill, but receives the full face value at maturity). During an auction round, the Treasury first sets aside a portion of the T-bills for non-competitive bids. The remaining T-bills are then auctioned off to the highest bidders on a sealed-bid basis. The set-aside portion is then sold at a discount equal to the average of the competitive bids.

Investors don't necessarily have to buy T-bills on their original issue. Trading in the secondary market is also possible. Since T-bills are issued weekly, the secondary market offers T-bills with a wide range of maturities. This allows investors to choose the maturity that best suits their investment horizon.

Treasury notes are government securities that mature in 2 to 10 years, whereas Treasury bonds mature in 10 to 30 years, though many treasury bonds are callable several years before their maturity (at most 5 years). Both Treasury notes and Treasury bonds are offered at prices and yields set in advance. Investors place their orders for new issues, and these orders are filled (possibly in part, depending on supply) at the yield set by the Treasury. Both Treasury notes and Treasury bonds are subject to maturity risk, because they take a longer time to mature than T-bills.

Dealers play a central role in the market for Treasury securities. New dealers must meet certain requirements to be able to participate in the market. They are subject to oversight by the Federal Reserve (e.g. they must report their positions in Treasury securities regularly), though the Federal Reserve does not directly regulate the market, i.e. dealers are free to arrange their own transactions with each other.

Returns from Treasury securities are subject to federal income tax, but not state or local income tax. They are also subject to other taxes (both federal and state), such as inheritance, estate, or gift taxes.

US Treasury securities are owned by various groups. For instance, as of September 2015:

- 41.3% were held by the Federal Reserve;

- 33.6% were held by foreign and international investors;

- 6.0% were held by mutual funds;

- 3.5% were held by state and local governments;

- 2.8% were held by depository institutions;

- 2.8% were held by pension funds;

- 1.6% were held by insurance companies;

- 7.4% were held by other investors.

The maturity distribution of Treasury securities also varies. For example, as of September 2015:

- 28.1% mature in less than 1 year;

- 42.0% mature in 1-5 years;

- 20.1% mature in 5-10 years;

- 1.8% mature in 10-20 years;

- 8.0% mature in over 20 years.

The Treasury tries to maintain a balance between short-term and long-term securities, or at the very least, it tries to avoid having too many short-term securities, which can generate other problems. For example, if there are too many short-term securities, and interest rates rise, the values of these securities will fall, which may introduce shocks to the financial system. Moreover, the Treasury must frequently issue new short-term securities to replace maturing ones, which can be an operational/administrative burden.

Term or maturity structure of interest rates

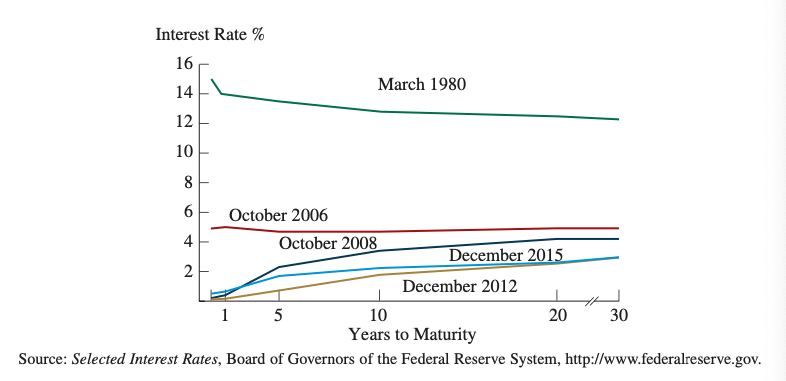

Term structure of interest rates refers to the relationship between interest rates and the time to maturity of debt instruments. The graphic representation of this relationship is called the yield curve. Yield curves:

- reflect securities with similar risk characteristics;

- represent particular points in time;

- show yields on a number of debt instruments with different maturities.

The following figure shows the yield curves for treasury securities at selected dates:

During the early 1980s, although the economy was in a mild recession, the Fed kept interest rates (the federal funds rate, which is the rate at which banks lend to each other) high to combat inflation:

high interest rates → high cost of borrowing → less borrowing by businesses and consumers → less investments → reduced demand for labor → higher unemployment → lower wages → lower consumer spending → reduced demand for goods and services → businesses lower prices → lower inflation

Once inflation is under control, the Fed can lower interest rates to stimulate the economy, as it did in the late 80s:

low interest rates → low cost of borrowing → more borrowing → more business investments → increased demand for labor → higher wages → higher consumer spending → businesses earn more → businesses invest more → higher GDP

After the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed lowered interest rates to near-zero levels partly to stimulate the economy, but also to avoid a deflationary spiral. Lower interest rates encouraged borrowing and spending, which wasn't happening because everyone was pessimistic about the outlook of the economy (e.g. businesses and consumers are saving, banks are holding onto reserves). The monteray policy measures taken by the Fed weren't enough to stimulate the economy, and since the Fed can't lower interest rates below zero, it had to resort to other measures. After rates were cut, the Fed continued to provide liquidity to the financial system through quantitative easing (i.e. buying government securities to inject money into the economy). The federal funds rate was kept near zero for several years, until it was raised to 0.25%-0.50% in late 2015.

Historical data suggests that interest rates generally rise during periods of economic expansion and fall during recessions. We can therefore look at the term structure of interest rates (i.e. yield curves) as indicators of the state of the economy:

- interest rate levels are lowest at the bottom of a recession;

- interest rate levels are highest at the peak of an expansion;

- yield curves slope upwards during expansions (i.e. economic recovery);

- yield curves flatten when economic activity peaks;

- yield curves invert when the economy is about to enter a recession.

Term structure theories

There are three main theories that explain the term structure of interest rates. The expectations theory holds that the yield curve reflects investor expectations about future inflation rates: flat, downward sloping, and upward sloping yield curves indicate that investors expect inflation to remain constant, fall, or rise, respectively.

The liquidity preference theory holds that investors prefer short-term debt instruments because they are more liquid than long-term debt instruments. Thus, investors are willing to accept lower yields on short-term debt instruments to compensate for the liquidity risk and maturity/interest rate risk of long-term debt instruments.

The market segmentation theory holds that the yield curve reflects the supply and demand for debt instruments with different maturities. In other words, securities with different maturities are not substitutes for each other, and investors are only interested in securities with maturities that match their investment horizons. For example, banks concentrate their holdings in short-term securities, because they need to maintain liquidity to meet deposit withdrawals. Insurance companies, on the other hand, concentrate their holdings in long-term securities, because they need to match their long-term liabilities with long-term assets.

Inflation premiums and price movements

Changes in the value of money (i.e. inflation/deflation) or changes in the supply of money can affect the whole economy. As the value of money or the supply of money changes, the supply of loanable funds changes, which affects interest rates, and in turn, both the supply of and demand for goods and services.

Inflation is an increase in the price of goods and services that is not offset by an increase in the quality of goods and services. When investors expect higher inflation rates, they demand higher interest rates to compensate for the loss of purchasing power.

Some historical examples of inflation include:

- inflation occured in Greece after Alexander the Great conquered Persia and took a large amount of gold back to Greece; the money supply increased, and as more money chased the same amount of goods and services, prices rose;

- inflation occured in Rome after the conquest of Egypt; moreover, Roman rulers debased the currency by reducing the amount of precious metals in coins, resulting in a degradation in the purchasing power of money, and consequently in higher prices; (one ruler, Aurelian, tried to restore the value of the currency by issuing new coins with higher precious metal content, but this was met with such resistance that an armed rebellion broke out);

- inflation occured throughout Europe in the 16th century when Spain imported large quantities of gold and silver from Mexico and Peru;

- inflation occured prior to the French Revolution, when the French government issued paper money to address its financial problems: it printed more money than it could back with gold and silver;

- inflation occured during the Revolutionary War, when the Continental Congress issued paper money to finance the war (they had no authority to levy taxes, so they printed money instead);

- during the War of 1812, the US government issued "paper money" (bonds bearing no interest and having no maturity date) to finance the war; the price of these bonds rose from 131 (1812) to 182 (1814);

- the US government issued paper money to finance the Civil War;

- the US government raised taxes and issued bonds heavily to finance war efforts during WWI and WWII.

In the 1979s, the US experienced high inflation rates, which were partly due to the Vietnam War (increased federal budget deficits), and partly due to the oil crisis (OPEC raised oil prices as a response to US support of the Israeli military during the Yom Kippur War). The Fed tried to combat inflation by raising interest rates (through monetary policy measures), but this approach did not work: both inflation and unemployment rose (i.e. stagflation; economists at the time believed that high inflation rate would lead to lower unemployment). The Fed (Volcker et al.) eventually abandoned the approach of targeting interest rates and instead focused on solely targeting the money supply. In the first three quarters of 1980, the Fed implemented monetary restraint to try to reduce inflation, but quickly reversed course when the economy entered a recession. However, the economy continued to worsen, as interest rates remained high (lenders demanded higher interest rates to compensate for the loss of purchasing power due to inflation). The Fed reversed course again and reimplemented monetary restraint, this time over a longer period of time. The economy slowed down again, but this time inflation also fell. By the end of 1982, the economy began to recover, and the Fed began to ease its monetary restraint.

Types of inflation

There are several types of inflation:

- cost-push inflation: price increases due to higher production costs; when production costs rise, businesses may raise prices to maintain profit margins, or they may reduce production, leading to shortages and higher prices (if demand remains constant);

- demand-pull inflation: price increases due to large increases in the money supply, which leads to increased demand for goods and services; when the money supply increases (e.g. through government spending), credit is more readily available, and businesses and consumers are more willing to borrow and spend, which increases demand for goods and services;

- speculative inflation: price increases due to expectations of future price increases; for example, when prices rise at the beginning of an inflation, people may expect prices to rise further, so they buy goods and services now to avoid paying higher prices later, which in turn causes prices to rise even further;

- administrative inflation: price increases due to government policies or some other union-corporation agreement; for example, some employment contracts have cost-of-living adjustments, which automatically raise wages when prices rise, which in turn raises prices further;

Default risk premiums

All investments have some risk, and investors demand higher returns to compensate for the risk of default. Default risk is the risk that the borrower will not be able to repay the loan, and the default risk premium is the additional expected return to compensate for this risk.

One way to estimate the default risk premium is to look at the difference between the interest rates of corporate bonds and government bonds (assuming that government bonds are free of default risk). For example, if the interest rate of a corporate bond is 5% and the interest rate of a government bond is 3%, the default risk premium is 5% - 3% = 2%.

Bond ratings are used to assess the default risk of corporate bonds. The three major credit rating agencies are Moody's, Standard & Poor's, and Fitch. These agencies assign ratings to corporate bonds based on the issuer's ability to repay the loan. Investment grade bonds have ratings of Baa or higher, whereas high-yield/junk bonds have ratings lower than Baa. A financial institution may or may not invest in junk bonds, depending on its risk tolerance.